Table of content

- GENERAL RELATION BETWEEN DEVELOPMENT AND EXTREMISM

- NAXALBARI OR MAOISM MOVEMENT

- INSURGENCY IN NORTH-EAST REGION

- INSURGENCY IN JAMMU & KASHMIR

General relation between Development and Extremism

There is a complex and multifaceted relationship between the development and spread of extremism.

- Some scholars argue that extremism can arise in situations where individuals or groups feel marginalized, oppressed, or excluded from mainstream society. In such circumstances, people may feel a sense of frustration, anger, and hopelessness, which can fuel extremist ideologies and actions.

- On the other hand, economic development and prosperity can also play a role in mitigating the spread of extremism. Countries with strong economies and high levels of employment tend to have lower rates of extremist activity, as people feel more secure and have less incentive to resort to violence or extremist ideologies. Additionally, education and access to information can help to counter extremist narratives and beliefs, as individuals become more informed and better equipped to critically evaluate extremist propaganda.

- However, it is important to note that the relationship between development and extremism is not necessarily straightforward. In some cases, economic development may exacerbate underlying tensions and lead to increased extremism. For example, rapid economic growth can result in uneven distribution of wealth, which may fuel resentment and exacerbate existing social and political divisions. Development and security together lay the foundations for sustainable peace.

In Indian Context

- Everyone has the right to a better standard of living, which includes having access to adequate food, clothing, housing, a high-quality education, good health, and a dignified way of life.

- We know from history that people revolt against colonial authorities when they lack these necessities. Extreme means were used by the common people to assert their rights due to the lack of development.

- When people realize that the government is not taking care of their needs, underdevelopment creates the conditions for insurgency and the spread of extremist ideologies.

- Today, governments all over the world have a policy of putting an emphasis on inclusive development. However, there are always groups in every state that feel alienated because they are not included in the development efforts.

- Extremism and militancy thrive in the context of these perceptions and corrupt and ineffective governance. More than a lack of development, the absence of efforts, mismanagement, and inability of the system to include marginalized communities contribute to extremism and violence. Naxalism, or left-wing extremism, is a prime example of the connection between extremism and development in India.

Forms of Extremism in India

NAXALBARI OR MAOISM MOVEMENT

- Naxalism, also known as Maoism, is a left-wing extremist movement in India that seeks to overthrow the Indian government through armed revolution. The movement takes its name from the village of Naxalbari in the state of West Bengal, where it originated in 1967.

- The Naxalite movement is characterized by its Maoist ideology, which emphasizes the need for armed struggle and violent revolution to overthrow capitalist and feudal systems of government. The movement has historically focused on rural areas, where it seeks to mobilize peasants and agricultural laborers in support of its revolutionary goals.

Reasons for naxalism

- Tribal people’s discontent with the government: The Forest (Conservation) Act of 1980 prohibits tribes whose livelihoods depend on forest products from even harvesting bark. In states affected by naxalism, massive tribal population displacement as a result of development projects, mining operations, and other factors. Maoists convert those without a means of income to naxalism by taking advantage of them.

- Economic reasons: Joblessness, destitution, an absence of medical services, an absence of training and mindfulness, an absence of admittance to power, web network, and correspondence, to give some examples issues.

- Loss of Common property resources (CPR): CPR makes a huge commitment to the provincial economy and supports neighborhood networks. CPR can be seen in village tanks, watershed drainages, and community pastures. The CPRs region is diminishing because of industrialization, privatization, and improvement drives, and the public authority never investigates it.

- Land rights: Land is a valuable resource in India, and disputes over land ownership have been a major driver of Naxalism. The Naxalites have mobilized landless peasants and tribal communities who have been displaced from their land by the government or private corporations.

- Government neglect: The Naxalites have been able to gain support from local communities in areas where the government has failed to provide basic amenities like healthcare, education, and infrastructure.

- Ideology: The Naxalites are driven by a Marxist-Leninist ideology, which seeks to overthrow the Indian state and establish a classless society. This ideology has resonated with some sections of the population who feel that they have been excluded from the benefits of India’s capitalist economy.

Impact of naxalism

- Violence: The Naxalite movement has been responsible for a significant amount of violence in India, including attacks on police and government officials, as well as bombings and assassinations.

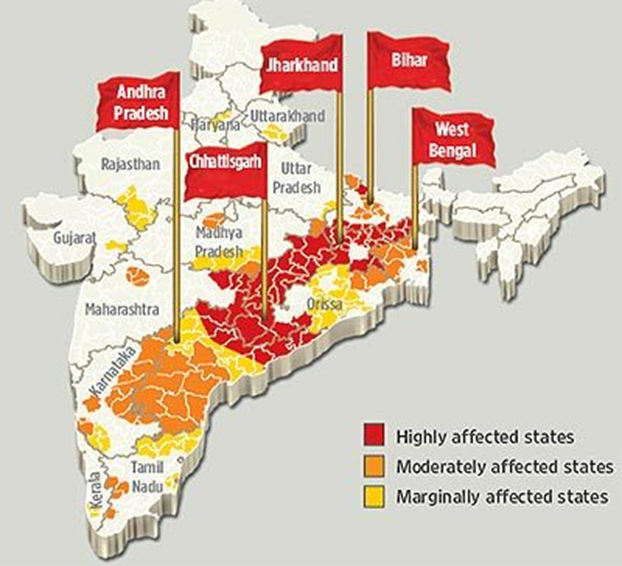

- Spread to multiple states: The movement is estimated to have between 6,000 and 10,000 active members, and is believed to have a significant presence in several Indian states, including Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Odisha.

- Political and social Instability: Naxalism has led to political instability in many parts of India. The insurgency has been active in several states, including Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Odisha, Bihar, and West Bengal, and has disrupted the normal functioning of these states.

- Economic Loss: The Naxalite movement has resulted in significant economic loss to the affected states. The insurgency has disrupted economic activities, including mining, agriculture, and other businesses. The Naxalites also extort money from businesses and individuals, further hurting the economy.

- Violence and Human Rights Violations: Naxalism has led to widespread violence and human rights violations in the affected regions. The Naxalites have attacked government institutions, police, and civilians. They have also engaged in extortion, kidnapping, and killing of civilians.

- Developmental Issues: The insurgency has hampered development in the affected regions. Many development projects, such as roads, bridges, and schools, have been disrupted due to Naxalite violence.

- Despite these efforts, Naxalism remains a significant challenge for the Indian government, particularly in the eastern and central parts of the country where the movement is most active.

Step to counter naxalism

- Measures Related to Law: The State enacted protective laws and made policy decisions in response to the ongoing unrest and social discord in areas dominated by scheduled castes and tribes. In order to protect these communities from being exploited in a variety of ways, it is necessary to construct an impenetrable protective shield for the state. This should be accomplished through the effective application of the existing constitutional provisions, civil rights protection, and SC/ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act laws and programs.

- Land-related Measures: Since about two to three decades ago, efforts to put ceiling laws into effect have stopped, as if there is no way to find excess ceiling land in the future. This isn’t true. In order to distribute the surplus land obtained from the land ceiling to the most disadvantaged members of the landless poor, consistent efforts must be made to implement the laws.

- Acquisition of Land, Rehabilitation, and Resettlement: Land acquisition has emerged as the single most significant factor in the involuntary displacement of tribals and the loss of their land. Land acquisition for public purposes should be limited to matters of national security and public welfare, and indiscriminate land acquisition should be stopped.

- Need for accommodation: Negotiations alone cannot combat extremism. It is evident that “dialogue” and “accommodation” are easier to find acceptance when the State’s good intentions and its desire to restore order are simultaneously visible, despite the fact that the situation necessitates the use of political and other non-police methods of handling it.

- Good governance would necessitate a clean, corrupt, and accountable administration at all levels, which would necessitate giving development work and its practical implementation a high priority.

- Building capacity of administration: The exercise should involve the public, the intelligence collection system, security agencies, and civil administration. According to the Report on Crisis Management, the strategy ought to incorporate efforts for prevention, mitigation, relief, and rehabilitation.

Steps taken by government to counter Naxalism

The Indian government has responded with a variety of measures, including military operations, anti-insurgency laws, and development programs aimed at addressing the underlying economic and social grievances that fuel the movement.

- Green Hunt operation: started in 2010 for deployment of security forces in the naxal-affected areas. Members of Central Committee Politburo of communist parties have either been killed or arrested.

- Surrender cum rehabilitation policy: The government even started ‘Relief and Rehabilitation Policy’ for bringing naxalites into mainstream.

- Aspirational Districts Programme: Launched in 2018, it aims to rapidly transform the districts that have shown relatively lesser progress in key social areas.

- The SAMADHAN initiative: it is the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA)’s answer to the Naxal problem. It encompasses the entire strategy of government from short-term policy to long-term policy formulated at different levels. SAMADHAN stands for-

- S- Smart Leadership,

- A-Aggressive Strategy,

- M- Motivation and Training,

- A- Actionable Intelligence,

- D- Dashboard Based KPIs (Key Performance Indicators) and KRAs (Key Result Areas),

- H- Harnessing Technology,

- A-Action plan for each Theatre,

- N- No access to Financing.

Achievements the efforts

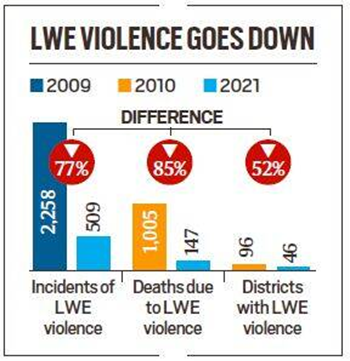

- From 223 districts that were affected due to naxalism in the year 2010, the number has come down to 90 in 2020.

- The incidents of LWE violence have reduced by 77% from an all-time high of 2,258 in 2009 to 509 in 2021. Similarly, the resultant deaths (civilians + security forces) have reduced by 85% from an all-time high of 1,005 in 2010 to 147 in 2021.

- According to reports, the Naxalite movement is facing a vacuum in the leadership, leading to the weakening of cooperation and coordination of the individual militants. The successful elimination of prominent leaders of the insurgent groups through various counterinsurgency operations has worsened the situations for the LWE groups.

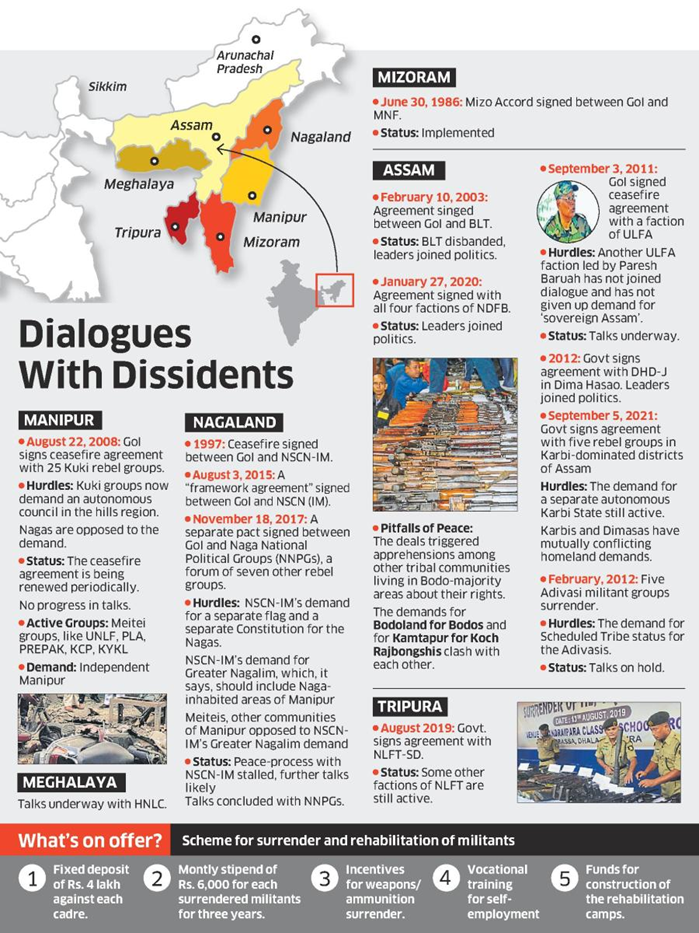

INSURGENCY IN NORTH-EAST REGION

The North East region of India comprises eight states – Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland, Sikkim and Tripura – each with its own distinct history and identity. The region shares its borders with Bhutan, China, Myanmar and Bangladesh and has been one of the most sensitive regions in India. Since 1947, the history of this region has been marred with insurgency and under development.

Origin and current situation of emergency in India

- Armed insurrections in the region began with a fleeting revolt by the Shanti Sena in Tripura led by Bipulananda Kar Choudhury soon after the county gained independence in 1947. A branch of the Communist Party of India (CPI), the Shanti Sena demanded reforms in land laws and an end to the feudal regime of the erstwhile princely state in Tripura.

- The Naga National Council (NNC) then launched a armed campaign in the middle of the 1950s to demand an independent Nagaland. In this way, throughout the following couple of many years, secessionist outfits and associations requesting independence became dynamic in different conditions of the area, provoking the Indian government to release forceful counterinsurgency tasks and the proclamation of unique regulations like the armed Forces (Special Powers) Act 1958.

- For a number of decades, the insurgent groups in India’s Northeast were supported by a variety of factors. These organizations received training facilities and weapons from Pakistan and China. In addition, there were safe havens in neighboring Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar, and weapons were easily accessible.

- A significant number of its youth are unemployed. For many decades, these young people with no jobs added to these insurgent organizations’ ranks.

- Currently, around 40 insurgent outfits are active in the Northeast in as many as six out of the region’s eight states. Manipur has the maximum number of active insurgent groups, while Sikkim and Mizoram have almost none.

- These groups can be broadly divided into five categories with the largest number being outfits engaged in a peace process with the government with the goal of clinching a negotiated settlement. This category includes the Isak-Muivah faction of the National Socialist Council of Nagalim (NSCN-IM), pro-talks faction of the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) and over 20 outfits in Manipur belonging to the Kuki and Zomi communities.

How situation changed?

- The situation began changing in 2003 when Bhutan launched a military offensive to dismantle the camps and training centers of three militant outfits active in Assam and West Bengal.

- Five years later, a crackdown began in Bangladesh resulting in the capture of top rebel leaders. They were handed over to India.

- In 2019, some camps in Myanmar’s Sagaing Division were also eradicated by the Myanmar military

- A surrender policy was unveiled by the government in 1998, which was revised ten years later. Under this policy, a surrendered militant functionary is granted Rupees 400,000 (approximately $5,000), a monthly stipend of Rs 6,000 for three years, and vocational training for self-employment. Thousands of functionaries from all the northeastern states have availed the package over the past several years.

- In the Northeast, the Indian government has been following a carrot and stick policy, which has involved offers of negotiations to all armed outfits alongside pursuit of counterinsurgency operations. Rebel groups have entered into peace agreements with the government at regular intervals preceded by periods of ceasefire and submission of charters of demands.

Causes of insurgency in NE India

- A Region with Multiple Ethnic Groups: The most ethnically diverse area in India is NEI. It is home to approximately 40 million people, including 213 of the 635 tribes that the Anthropological Survey of India has listed2. Each of these tribes has its own distinct culture. As a result, each tribal sect despises being incorporated into mainstream India because it means losing their unique identity. Insurgencies to preserve one’s own culture rise as the GoI resorts to a variety of strategies for “integration” into the “mainstream” based on a limited understanding of peoples and tribes. Inter-tribal rivalries, which fuel tribal/ethnic insurgencies, exacerbate the situation.

- Region with limited development: In NEI, infrastructure development has generally been sluggish, frequently at a snail’s pace, due to the difficult terrain configuration of jungles and mountains. The division that exists between the NEI and mainstream India as a result of this has grown, as has dissatisfaction with the Government of India. People are also feeling resentment and unease as a result of the government of India’s economic policies.

- Feelings of Isolation, Deprivation, and Abuse: Distance from New Delhi and small portrayal in the Lok Sabha has additionally decreased the vox populi being heard in the passages of abilities, prompting greater bafflement in the exchange cycle, in this way settling on decision of the firearm more alluring.

- Changing demographics of the region: As a result of the influx of refugees from the former East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) into Assam, the demographics of the area underwent significant shifts. There were approximately 45,000 illegal immigrants on the voter rolls at the Mangaldai by-election in 1979.3 This caused discontent among the local population, which in turn led to Assam’s insurgency, led by the United National Liberation Front (ULFA), which was established on April 7, 1979.

- Interior Relocation: Internal displacement is another persistent issue. In episodes of inter-ethnic violence in western Assam, along the border between Assam and Meghalaya, and in Tripura, over 800,000 people were forced to flee their homes from the 1990s to the beginning of 2011. Due to the prolonged armed violence, approximately 76,000 people in NEI remain in internal displacement, according to conservative estimates.

- External Support: In the late 1950s, the former East Pakistan supported the insurgencies in the NEI; and at the beginning of the 1960s, in the form of arming and training members of the Naga Army. From 1967 to 1975, when China’s foreign policy advocated the spread of “revolution” throughout the world, Chinese support for the insurgency in India was at its highest. Later, China also provided moral support and weapons.

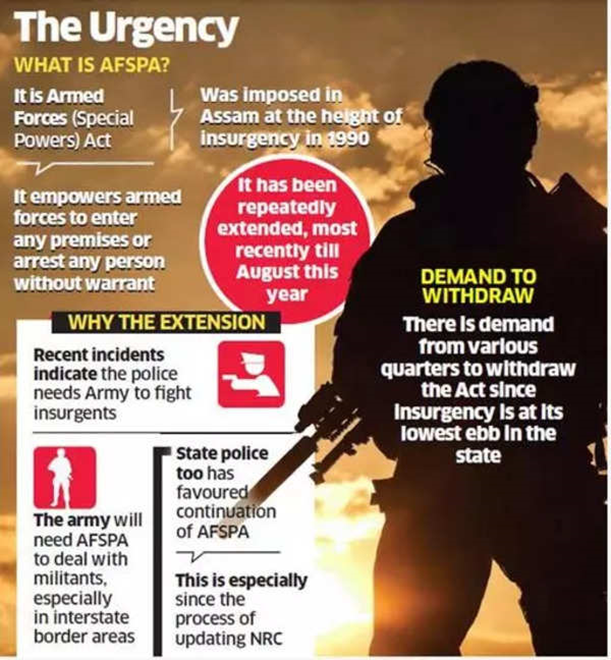

- Negative Perception about armed forces: Adoption of the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) has further alienated the local populace. Despite its importance in bolstering Indian Army’s ability to carry out Counter Insurgency operations, various Human Rights (HR) organizations frequently portray it as oppressive, and as a result, various insurgent groups have vilified it.

Current approach of the government

The Central government has identified three core objectives for the North East Region:

- to preserve its dialects, languages, dance, music, food, and culture and to create attraction for it all across India;

- to end all disputes in the North East and to make it a peaceful region,

- to make the North East a developed region and bring it on par with the rest of India

In this regard, various border dispute settlement agreements and peace accords have been signed with relevant stakeholders. Further, with the help of the armed forces, satellite camps of insurgent groups operating from foreign soil have also been neutralized at scale.

Major Agreements Signed to Bring Peace and Prosperity to the Northeast

Long pending disputes between various states in the Northeast had been a major concern in the development of the region. Many decades-long disputes are finally getting permanently resolved through the proactive efforts of the Central government. This has given a push to integration and trust and has paved the way forward for long-term peace and progress.

Bodo Accord: During the 1960s, the Bodos and other tribes of Assam called for separate state of Udayachal. In late 1980s, there was another demand for a separate state for Bodos – Bodoland, and for Assam to be divided “50-50”. As a result of these continuous demands, there had been widespread incidents of violence over the years. To resolve the five-decade old Bodo issue in Assam, the Bodo Accord was signed on January 27, 2020 resulting in the surrender of 1615 cadres with a huge cache of arms and ammunition at Guwahati.

Bru-Reang Agreement: Due to ethnic violence in the western part of Mizoram in October 1997, a large number of minorities Bru (Reang) families migrated to North Tripura in 1997-1998. A landmark agreement was signed on January 16, 2020, to resolve the 23-year-old Bru-Reang refugee crisis by which more than 37,000 internally displaced people are being settled in Tripura.

National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) Agreement: The National Liberation Front of Tripura (NLFT) formed in 1989 has been involved in violence, operating from their camps across international borders. After several years of negotiations with the Government of India and the Government of Assam, an agreement was signed with National Liberation Front of Tripura (SD) in August 2019 resulting in the surrender of 88 cadres with 44 weapons.

Karbi Anglong Agreement: The Karbis are a major ethnic group of Assam, whose history has been marked by killings, ethnic violence, abductions and taxation since the late 1980s. To resolve the long-running dispute in the Karbi regions of Assam, the Karbi Anglong Agreement was signed on September 04, 2021, in which more than 1000 armed cadres renounced violence and joined the mainstream of society.

Assam-Meghalaya Inter-State Boundary Agreement: A landmark agreement was signed on March 29, 2022, to settle the dispute over six areas out of a total of twelve areas of the interstate boundary dispute between the states of Assam and Meghalaya. This agreement alone resolved around 65 per cent of border disputes between the two states.

From Disturbed Area to Aspirational Area: As a result of the border dispute settlement agreements and peace accords, there has been a significant improvement in the security situation of the Northeast. The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) has been reduced from a large part of the North East.

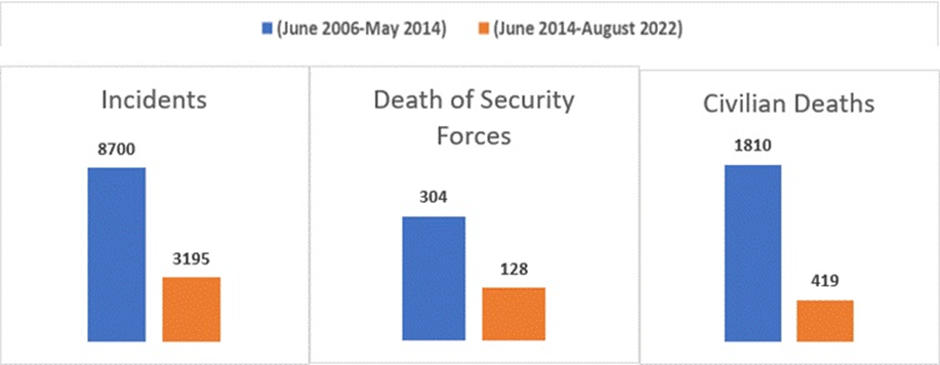

Achievements

- The security situation in the North-Eastern states has considerably improved since 2014. The year 2019 and 2020 witnessed the lowest number of insurgency incidents and casualties of civilians and security forces during the last two decades. In comparison to the year 2014, there has been a reduction of 80% in the incidents of insurgency in the year 2020.

- Similarly, during this period, the number of casualties in security forces decreased by 75% and civilian casualties decreased by 99%. While there were 824 incidents of violence in the Northeast in 2014 in which 212 innocent civilians were killed, it has reduced to 162 such incidents in 2020, in which only three civilians were killed. In the last two years, 4,900 militants have surrendered. Overall, a total of 6000 militants have surrendered since 2014.

- As a result of the border dispute settlement agreements and peace accords, there has been a significant improvement in the security situation of the Northeast. The Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) has been reduced from a large part of the North East, fulfilling the long-standing and sentimental demand of the North Eastern states.

- Assam: 60% of Assam now free from AFSPA

- Manipur: 15 police stations in six districts were taken out of the periphery of the disturbed area

- Arunachal Pradesh: Now AFSPA left in only three districts and two police stations in one district

- Nagaland: Disturbed area notification removed from 15 police stations in seven districts

- Tripura and Meghalaya: Completely withdrawn

How to improve further?

- Agreements for Peace: The GoI must sign peace agreements with various remaining insurgent groups in the region, similar to the “Framework Agreement” it signed with NSCN (IM) in August 2015, in order to guarantee peace and stability in NEI, even if it is only temporary. With the NSCN (K), ULFA, and other insurgent groups, a similar agreement might be signed. For conflict resolution to occur, insurgent groups must be actively and persistently engaged in discussions.

- Participation of Rebel Leaders. Now that ULFA’s General Secretary Anup Chetia, who was in prison in Bangladesh, has been brought back and released on bail in December 2015, he must serve as the GoI’s point man for further negotiations with ULFA that lead to a time-bound agreement.

- Progress Made by Civil Society: The civil society’s efforts to reconcile with the insurgent organizations must continue, despite the progress in peace talks. This makes it possible for the insurgent leaders to find a respectable way out of the situation, which benefits everyone involved.

- Enhanced Socio-Economic Growth: The Act East Policy The Government of India (GoI) needs to accelerate its plans for the region’s development in order to eliminate one of the insurgency’s primary causes. In order to instill a sense of oneness among the people of NEI, the construction of infrastructure like roads, hospitals, schools, and sanitation facilities is crucial.

- Focus on identity rather than “mainstreaming“: A “potpourri” of different tribes, ethnicities, religions, customs, languages, and so on can be found in NEI. As a result, these people’s individual identities should be prioritized more than mainstreaming them. While a political solution is being drafted, this will bring stability to the region and reduce their resisting power. It is reiterated that these operations must be conducted with compassion.

- AFSPA continuation: In areas with a high incidence of insurgency, it is highly recommended to maintain AFSPA.

- Replacing Indian Army: It is abundantly clear that the situation has stabilized in many parts of Assam and NEI as a result of the peaceful conduct of state elections in April 2016 in Assam. As a result, IA must return to the barracks and hand over these districts to the civil administration in these areas. The CRPF can step in and help the state police keep order in these areas if it’s necessary.

From Disturbed Area to Aspirational Area

- Making Northeast the Economic Hub of India

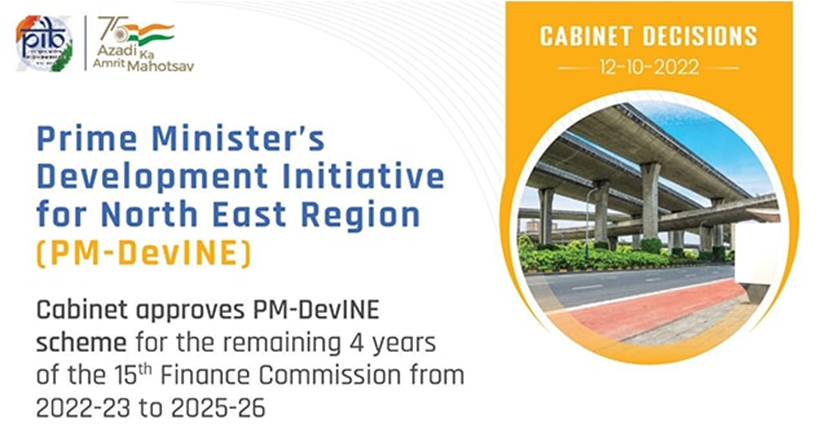

The government is committed to the all-round development of the Northeast region and making it an economic hub connecting Southeast Asia under the Act East Policy. The total earmarked funds under 10% gross budgetary support from 54 Central Ministries for expenditure on development works in the North East have been increased by 110% from Rs 36,108 crore in 2014-15 to Rs 76,040 crore in 2022-23.

- A new scheme, The Prime Minister’s Development Initiative for the North-East (PM-DevINE), was announced in the Union Budget 2022-23 with an initial allocation of Rs 1,500 crore.

- Act East Policy

‘Act East Policy’ announced in November 2014 is the upgrade of the ‘Look East Policy’ which was promulgated in 1992. The Objective of ”Act East Policy” is to promote economic cooperation, cultural ties and develop strategic relationships with countries in the Asia-Pacific region through continuous engagement at bilateral, regional and multilateral levels thereby providing enhanced connectivity to the States of North Eastern Region with other countries in our neighbourhood. The Act East policy is playing an instrumental role in bringing a paradigm shift and marking a significant change in the potential role of the North-East region.

INSURGENCY IN JAMMU & KASHMIR

- The low-intensity conflict in Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) has been the most important issue in India’s internal security scenario.

- Possession of the State has been an issue of dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947. After two unsuccessful attempts to seize the territory by force (1947 & 1965), Pakistan has largely refrained from making any direct attempt at challenging control in the area of J&K still in India’s possession.

- Rather, the focus of Pakistan’s efforts, channelled through the Inter Services Intelligence (ISI), is on aiding Pakistan-based militant groups who are waging a proxy war against Indian security forces in the State. With the two countries going overtly nuclear in 1999, the issue is also percieved globally as a nuclear flash point.

Reasons and Emergence of the insurgency in J&K

- Withdrawal of Soviet forces: The emergence of the protracted insurgency in J&K, which began with two explosions in 1988 (in Srinagar, the State capital), coincides with the withdrawal of Soviet forces from Afghanistan.

- Long phase of political turmoil: The insurgency was preceded by a long phase of political turmoil in the State, which began after the death of Sheikh Abdullah in 1982. Political squabbles between the National Conference and the Congress government at the Centre, saw the dismissal of two State governments. While Farooq Abdullah’s government was dismissed in 1984, the successor Ghulam Mohammad Shah government was dismissed in 1986.

- Congress and the NC formed an alliance to contest the State Assembly elections held in 1987. The alliance won and Farooq Abdullah was once again sworn in as Chief Minister of the State. The Congress-NC alliance was opposed, in the 1987 elections, by a coalition of Islamic parties, the United Muslim Front. Allegations of rigging in these elections gained wide credibility and generated domestic unrest in the State.

- Pakistan’s role: Pakistan set out to channelize this civilian discontent into an armed insurgency against India. Several training camps were now set up on the same model for disaffected elements who were willing to take up arms against India’s control in J&K.

- In July 1988, a series of demonstrations, strikes, and attacks on the Indian government effectively marked the beginning of the insurgency in Jammu and Kashmir, which escalated into the most severe security issue in India during the 1990s.

- The violent secessionist outbreak in 1989, and since then, the government’s anti-militancy and counterinsurgency operations, have embedded strong ‘Us vs Them’ narratives amongst the Kashmiris and alienated them from the Indian polity.

- These state actions have included crackdowns, arrests, killings of local militants, and heavy enforcement of laws such as the Public Safety Act (PSA) and the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA).

- Consequently, a negative perception of India and its policies has been nurtured; there is popular perception amongst the Kashmiri people of the Indian state being a “coloniser” or an “occupier”.

- The impacts of these perceptions have only been exacerbated in more recent years, amidst what analysts call “new militancy”—where the locals dominate the militant movement, and social media facilitates mass radicalisation and the spread of anti-India propaganda.

- It is in this context that India needs to exert greater effort in shaping its narratives to address the widespread negative perceptions and maintain its territorial integrity.

Abrogation of Article 370

- Article 370 of the Indian constitution was the temporary provision. This Article grants special status to the State of Jammu and Kashmir. Article 370 of the Constitution of India allows the State of Jammu and Kashmir to have their own Constitution. Many other laws apply to India, but the State of Jammu and Kashmir gets exempted from such laws.

- The abrogation of this special status (Article 370) of J&K on August 5, 2019 led many to speculate that there would be a substantial increase in terrorism-induced violence in the region following the decision. However, the security scenario has continued to improve from the preceding years to the extent that Doda was declared a terrorist-free district.

- As Jammu and Kashmir completes two years as a Union Territory (UT), militancy remains a major challenge to the security apparatus amid growing fears that the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan is likely to flip the striking capabilities of the militant outfits, especially the Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM) and the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM).

Impact of abrogation

Positive impacts

- After the constitutional changes and reorganization of the erstwhile State of Jammu-Kashmir, the Union territories of Jammu-Kashmir and Ladakh have been fully integrated into the mainstream of the nation.

- As a result, all the rights enshrined in the Constitution of India and benefits of all the Central Laws that were being enjoyed by other citizens of the country are now available to the people of Jammu-Kashmir and Ladakh.

- The change has brought about socio-economic development in both the new UT’s i.e. UT of Jammu-Kashmir and the UT of Ladakh. Empowerment of people, removal of unjust Laws, bringing in equity and fairness to those discriminated since ages who are now getting their due along with comprehensive development are few of the important changes that are ushering both the new Union Territories towards the path of peace and progress.

- With the conduct of elections of Panchayati Raj Institutions such as Panches and Sarpanches, Block Development Councils and District Development Councils, the 3-tier system of grassroot level democracy has now been established in Jammu and Kashmir.

Negative impacts

- Despite this trend, there has been a series of targeted killings in the region in recent months. Srinagar was the worst hit by violence with many hit-and-run attacks in 2021.

- The August 2019 abrogation of Jammu & Kashmir’s (J&K) special constitutional status under Article 370, which had limited the Indian parliament’s power to make laws for the state, prompted militant groups in Kashmir to change their tactics, including recruiting “hybrid militants” who are difficult to identify.

- New militant groups have emerged, including United Liberation Front of Kashmir (ULFK), The Resistance Force (TRF), Kashmir Tigers, and People’s Anti-Fascist Force (PAFF). These groups are also trying to project themselves as the true representatives of the people of Kashmir, their rights and suffering by focusing on resistance against Indian occupation instead of relying upon their former jihad or religious war narrative.

- Government claims that older terrorist organizations, such as Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) and JeM, have adopted new avatars to secularize their movement.

How the insurgency in Kashmir is different from the Maoist insurgency or the insurgency in NE?

- The insurgency in Kashmir is different primarily because it arises from differing perceptions with Pakistan and the people of Kashmir valley on the accession of the State of Jammu and Kashmir to the Indian Union at the time of independence and the special status accorded to the State through Article 370 of the Indian Constitution.

- The insurgency in J&K has been actively assisted by the Government of Pakistan and the two countries have fought in 1948, 1965, 1971, and in the Kargil sector on this issue. It has been the official policy of the Government of Pakistan to bleed India through a thousand cuts in order to weaken its resolve that J&K is an integral part of India.

- The Maoist insurgency originates from apparent discontent over agrarian reforms and exploitation of the local population, especially tribals; and now has the stated objective of the overthrow of the Indian State and parliamentary democracy. It has got its support by exploiting local grievances against the local government to organise an armed liberation struggle against the Indian State.

- It draws inspiration from Mao Tse Tung’s Communist movement. It is not limited to any one state since the Maoists do not believe in parliamentary democracy and is currently spread in parts of at least 9 States in India. Maoists have been reported to have got training from the LTTE and are actively seeking cooperation from insurgent groups in the North East, especially the PLA.

How to further improve situation in J&K?

- Role of social media: Virtual entertainment has turned into a significant wellspring of data — as well as falsehood and misleading publicity — in the hour of new hostility. Even though the government has taken preventative measures like imposing blanket bans, monitoring, censoring, and reporting extremist profiles and content, it has not been able to stop the dissemination of extremist content via social media.

- District Development Councils: The political focus in Kashmir shifted to District Development Councils (DDCs) and grassroots development after Jammu and Kashmir lost its statehood. The elected local leaders, who can ensure good governance and local development, offer new hope to Kashmiris who have endured bureaucratic red tape for a considerable amount of time.

- Use of Technology: India can increase its investments in technologies like unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drone technology and use them in peaceful locations. These technological tools can be used to conduct surveillance, uphold law and order, and discourage militants and their supporters from using drones. In order to discourage extremist content, the state will still need to invest in artificial intelligence (AI) and other technologies. It should also come up with creative ways for Kashmiris to consume the narratives produced by the Indian state and army.

- Promoting Education: The state ought to begin placing a renewed emphasis on education in the long run. The educational curriculum in Kashmir and the rest of India contains a variety of historical distortions and unfamiliarity. Promoting subjects and ideas that are more relatable and applicable, like constitutional remedies for people living in conflict-affected regions, is crucial.

Various Initiatives and scheme by the government of India

The government wants to use development as tool against the militancy in Kashmir for that it launched several initiatives:

- UDAAN was started with an aim to providing skill to the youth of valley.

- PM’s development package for J&K: under this government focused over creating the new avenues of employment and better infrastructure in transportation, health, renewable energy, tourism etc.

- Creating institute like AIIMS, IIT, and IIM construction of tunnel to reduce time lost in travelling.

- Project Himayat: capacity building and employment of youth.

- Project Sadhbhavana: of Indian army helping the youth in shaping their dream.

- Project Umeed: for empowerment of women.

- The Indian state and the armed forces are therefore attempting to enhance their nation-building narrative by supplementing traditional missions that seek to win hearts and minds, with social-media initiatives.

Conclusion

Development and internal security are, in many ways, two sides of the same coin. Each is completely reliant on the other. Often, a lack of progress and few chances for bettering one’s lot provides fertile ground for radical views to thrive.

A high majority of extremist organization recruits come from disadvantaged or marginalized backgrounds, or from locations that appear to be unaffected by the country’s booming expansion.