- Courses

- GS Full Course 1 Year

- GS Full Course 2 Year

- GS Full Course 3 Year

- GS Full Course Till Selection

- Answer Alpha: Mains 2025 Mentorship

- MEP (Mains Enrichment Programme) Data, Facts

- Essay Target – 150+ Marks

- Online Program

- GS Recorded Course

- Polity

- Geography

- Economy

- Ancient, Medieval and Art & Culture AMAC

- Modern India, Post Independence & World History

- Environment

- Governance

- Science & Technology

- International Relations and Internal Security

- Disaster Management

- Ethics

- NCERT Current Affairs

- Indian Society and Social Issue

- NCERT- Science and Technology

- NCERT - Geography

- NCERT - Ancient History

- NCERT- World History

- NCERT Modern History

- CSAT

- 5 LAYERED ARJUNA Mentorship

- Public Administration Optional

- ABOUT US

- OUR TOPPERS

- TEST SERIES

- FREE STUDY MATERIAL

- VIDEOS

- CONTACT US

State of Social Protection Report 2025

State of Social Protection Report 2025

14-04-2025

Introduction

- Recently “The State of Social Protection Report 2025: The 2-Billion-Person Challenge”, published by the World Bank in April 2025, offers the most comprehensive global review of social protection systems across 186 low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

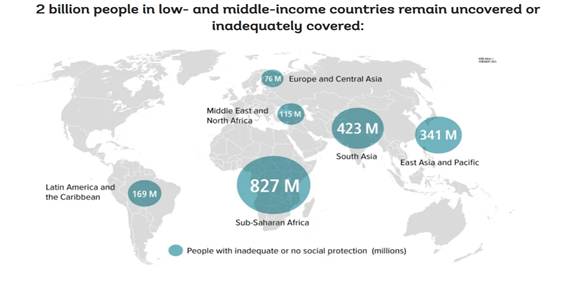

- The report highlights the “2-Billion-Person Challenge”, referring to the two billion people in LMICs who remain completely uncovered or inadequately protected by any form of social protection, especially in fragile, conflict-affected, and poverty-prone regions.

- Drawing from the World Bank’s ASPIRE database, the report assesses global trends in coverage, adequacy, and public spending, and aligns with SDG 1.3, calling on countries to build universal, inclusive, and shock-responsive social protection systems.

What is Social Protection?

- Social protection refers to a set of public measures that protect individuals and families against economic and social distress, aiming to ensure a minimum level of well being for all across their life cycle.

- It rests on three main pillars:

-

- Social Assistance (e.g., cash transfers, food aid),

- Social Insurance (e.g., pensions, health insurance),

- Labor Market Programs (e.g., skills training, public employment services).

- These programs help people escape poverty, manage shocks and transitions (e.g., job loss, disability, natural disasters), and seize employment opportunities in a changing world.

- Social protection systems also generate significant local economic multipliers. According to the report, each dollar transferred to poor households can yield up to $2.50 in increased economic activity, supporting both poverty reduction and inclusive growth.

Key Findings from the 2025 Report

- Social protection coverage has reached a historic high — expanding to 4.7 billion people in LMICs over the past decade. Coverage increased from 41% in 2010 to 51% in 2022, with the sharpest gains among the poor in LICs.

- Despite significant progress, 2 billion people in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) remain uncovered or inadequately protected by any form of social protection. This includes 1.6 billion people receiving no benefits and 400 million receiving insufficient support.

- Uncovered populations are concentrated in fragile, conflict-affected, and hunger-prone regions, including South Asia, the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa.

- At current rates, it will take 18 years to fully cover people living in extreme poverty, and 20 years to cover the poorest 20% of households in LMICs

- Coverage disparities are sharp across income groups:

-

- In low-income countries (LICs), over 80% lack coverage, and 3 out of 4 people receive no assistance.

- In lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), 58% remain uncovered.

- In upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), around 11% are entirely excluded.

- Social assistance — particularly cash transfers and school feeding programs — has been the main driver of expansion, especially in LICs. However, benefit adequacy remains low, covering only 11% of poor household income in LICs.

- Social protection spending is grossly unequal:

- LICs: less than 2% of GDP

- LMICs: 3.7%

- UMICs: over 6%

- The COVID-19 pandemic served as a global stress test: emergency responses reached 1.7 billion people, but countries with pre-existing robust systems were better able to scale up support.

- Gender inequality persists: In a 27-country sample, women received only $0.81 for every dollar transferred to men, despite higher overall female enrollment in programs.

- Labor market programs remain underutilized, reaching only 5% of the population on average, despite their strong potential to improve employment, earnings, and productivity. Programs like public works, job placement services, and unemployment insurance are constrained by low global funding, with average spending at just 0.25% of GDP.

India’s Position – Progress and Gaps

- India has expanded its social protection footprint, with coverage rising from 24.4% in 2021 to 48.8% in 2024. Nearly 65% of the population now receives at least one benefit — either cash or in-kind.

- Still, over 90% of India’s workforce is employed informally, and only 22% of informal workers are covered under any structured social protection scheme.

- Strong regional disparities persist: Tamil Nadu and Kerala offer relatively comprehensive systems, while Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, and parts of the East face major delivery and coverage gaps.

- Major schemes like eShram (30.68 crore registrations), Atal Pension Yojana (7.25 crore subscribers), Ayushman Bharat, PM-SYM, and PMGKAY have expanded coverage. However, overlaps between Ayushman Bharat and state-run health schemes have created confusion among beneficiaries.

- India's welfare architecture suffers from fragmentation, with multiple schemes spread across departments, leading to inefficiencies, duplication, and difficulties in access.

- The absence of a unified worker registry complicates beneficiary identification, causing both inclusion and exclusion errors. Many eligible individuals remain unaware of their entitlements due to weak outreach mechanisms.

- Persistent gender gaps, particularly in rural and informal settings, restrict women’s access to digital platforms and benefit delivery, compounding economic vulnerability.

- Portability issues hinder access to benefits for interstate migrant workers, as current systems are not fully interoperable across state boundaries.

- While social sector spending was around 21% of the Union Budget for much of the last decade, recent stagnation in allocations raises concerns of under investment in critical welfare infrastructure.(The share declined to 17% in 2024-25 and is projected at 19% for 2025-26)

Challenges in Expanding Social Protection Coverage

- Inadequate Coverage and Fragmentation: Social protection systems cover only about half the population in LMICs, and many schemes operate in silos, resulting in fragmented delivery. Multiple ministries run overlapping programs, limiting integration and reducing overall system impact.

- Weak Inclusion of Informal Workers: Over 90% of workers in LICs are informally employed, yet most social protection schemes are designed around formal sector employment. This leaves the majority excluded, especially those with the capacity to contribute to social insurance.

- Low Adequacy of Benefits: In LICs, social assistance covers only 11% of a poor household’s income. Across countries, benefits often fall below poverty thresholds, making them ineffective in helping people escape poverty or cope with shocks.

- Severe Fiscal Constraints and Inefficient Spending: LICs spend less than 2% of GDP on social protection. Many countries rely heavily on international grants, while existing funds are often consumed by regressive subsidies (e.g., fuel, agriculture), instead of reaching the vulnerable.

- Limited Shock-Responsiveness: Though crises like COVID-19 showed the need for adaptive systems, few countries have dynamic registries, early warning tools, or pre-arranged risk financing to respond effectively to future shocks.

- Design and Delivery Gaps: Many programs suffer from poor targeting, exclusion errors, and a lack of interoperable digital systems. There is also a need for greater investment in labor market programs, which remain underfunded and under-scaled, especially in LICs where coverage is below 5%.

Recommendations from the Report

- Reach the Uncovered First: The report stresses the need to prioritize the poorest and most excluded. In low-income countries, this means expanding non-contributory schemes like cash transfers and livelihood support. In middle-income countries, the focus should be on covering informal workers, improving access to pensions, insurance, and job-related programs.

- Make Benefits More Meaningful: Simply enrolling people is not enough. Many poor households receive very low benefits that don’t protect them from poverty or shocks. Countries need to ensure benefits are adequate, timely, and matched to real needs — including gender-sensitive adjustments in how support is designed and delivered.

- Prepare for Future Crises: Shocks like pandemics, floods, or job losses can push vulnerable families deeper into poverty. The report calls for building shock-ready systems — using digital databases, early warning tools, and flexible program rules to respond quickly during emergencies.

- Use Resources Better: Many countries spend heavily on inefficient subsidies (like fuel or agriculture) that don’t reach the poor. The report suggests shifting this money to targeted programs. Governments should also invest in digital tools and improve coordination to make every rupee count.

Conclusion

- Expanding social protection is no longer optional — it is essential to reduce poverty, manage risk, and promote economic resilience, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

- With over 2 billion people still uncovered or insufficiently protected, there is an urgent need to build universal, inclusive, and shock-ready systems that respond to real-world challenges.

- Achieving the vision of SDG 1.3 requires a fundamental shift — from fragmented safety nets to integrated, lifecycle-based social protection that upholds dignity and secures livelihoods for future generations.

Appendix A: Country Classification by Income (World Bank 2023)

|

Income Group |

GNI per Capita (2023) |

Examples |

|

Low-Income Countries (LICs) |

$1,145 or less |

Ethiopia, Chad |

|

Lower-Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) |

$1,146 – $4,515 |

India, Nigeria |

|

Upper-Middle-Income Countries (UMICs) |

$4,516 – $14,005 |

China, South Africa |

|

High-Income Countries (HICs) |

More than $14,005 |

United States, Germany |

Appendix B: ASPIRE Database Explained

- ASPIRE stands for the Atlas of Social Protection Indicators of Resilience and Equity.

- It is developed by the World Bank to evaluate social protection systems globally.

- The State of Social Protection Report 2025 uses ASPIRE as its primary data source.

- ASPIRE covers data from over 140 countries, integrating household surveys and administrative records.

- It provides standardized indicators on:

a) Coverage – share of population receiving benefits

b) Adequacy – size of benefits relative to income

c) Spending – public expenditure as % of GDP

d) Equity – how benefits are distributed across income groups and genders - The database is validated by national statistics offices and curated by the World Bank’s Poverty and Equity Global Practice.

- ASPIRE supports cross-country comparisons, evidence-based policymaking, and reform tracking.

- It plays a central role in assessing progress toward SDG 1.3 on universal social protection.

Appendix C – SDG 1.3: Social Protection and Global Goals

- Sustainable Development Goal 1.3 is part of the UN 2030 Agenda, aimed at ending poverty in all its forms everywhere.

- SDG 1.3 specifically calls for countries to:

“Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable by 2030.” - The goal emphasizes both universal protection (all citizens) and targeted support (for the most vulnerable).

- Key components of SDG 1.3 include:

a) Expanding social assistance (e.g., cash transfers, food security programs)

b) Strengthening social insurance (e.g., pensions, health coverage)

c) Integrating labor market programs (e.g., job guarantees, skills training) - SDG 1.3 aligns directly with the World Bank’s call for universal, adequate, and shock-responsive systems in the State of Social Protection Report 2025.

- Progress is tracked using indicators like population coverage, benefit adequacy, and spending as a % of GDP.

- Many low-income countries are still far from meeting the target due to coverage gaps, fiscal limitations, and data challenges.

- The World Bank, ILO, and national governments are working to accelerate reforms that bring countries closer to achieving SDG 1.3 by 2030.

|

Also Read |

|

| FREE NIOS Books | |